NASA's Kepler Space Telescope mission has just announced the discovery of 1,284 new exoplanets - nine of which are considered potentially habitable.

This is the most new planets announced at any one time, and almost doubles the number of confirmed exoplanets out there in the Universe, which makes it a pretty huge deal. The discoveries were made using a new technique that allows scientists to assess the likelihood that blips in the data really are planets, and aren't the result of other astronomical objects.

"This announcement more than doubles the number of confirmed planets from Kepler," said Ellen Stofan, chief scientist at NASA Headquarters. "This gives us hope that somewhere out there, around a star much like ours, we can eventually discover another Earth."

When Kepler looks for exoplanets, it looks at the light coming from distant stars. Any sign of that light dimming slightly before it gets to Kepler could be a result of a planet passing in front of its sun.

That's the best system we have so far, but it can also lead to a whole lot of false positives because planets aren't the only thing that can dim a star's light - for example, it could be a binary star system, a brown dwarf, or a low-mass star.

To confirm what's going on, in the past we've had to follow up on each of those candidate planet observations one at a time using ground-based telescopes, which is incredibly time-consuming and expensive. It's one of the reasons we were only able to confirm 984 exoplanets before this, despite seven years of the Kepler mission.

But the new validation technique assesses the probability that planet candidates really are planets en masse, without any follow-up required.

"Imagine planet candidates as bread crumbs," Timothy Morton from Princeton University in New Jersey, who developed the new technique, said in a live press briefing. "If we drop a few on the ground we can pick them up one by one. But if you spill a whole bucket full of small crumbs, you're going to need a broom to clean them up."

This new technique is that metaphorical broom. It works by calculating two things: first, how much the shape of a candidate planet's transit signal looks like a planet, statistically speaking; and secondly, how common false positives 'imposter candidates' are out there.

Putting this information together gives scientists a reliability score between zero and one for each planet candidate. And candidates with a reliability greater than 99 percent can now be called 'validated planets,' without having to perform any follow-up observations.

Morton cross-checked this new method with the data from ground-based follow-ups in the past and found that his predictions matched up almost perfectly with what telescopes had seen. "For every planet that the ground-based surveys measure to be a planet, I predict it should be a planet," Morton said, "and everything they measure to be a false positive, I predict to be a false positive."

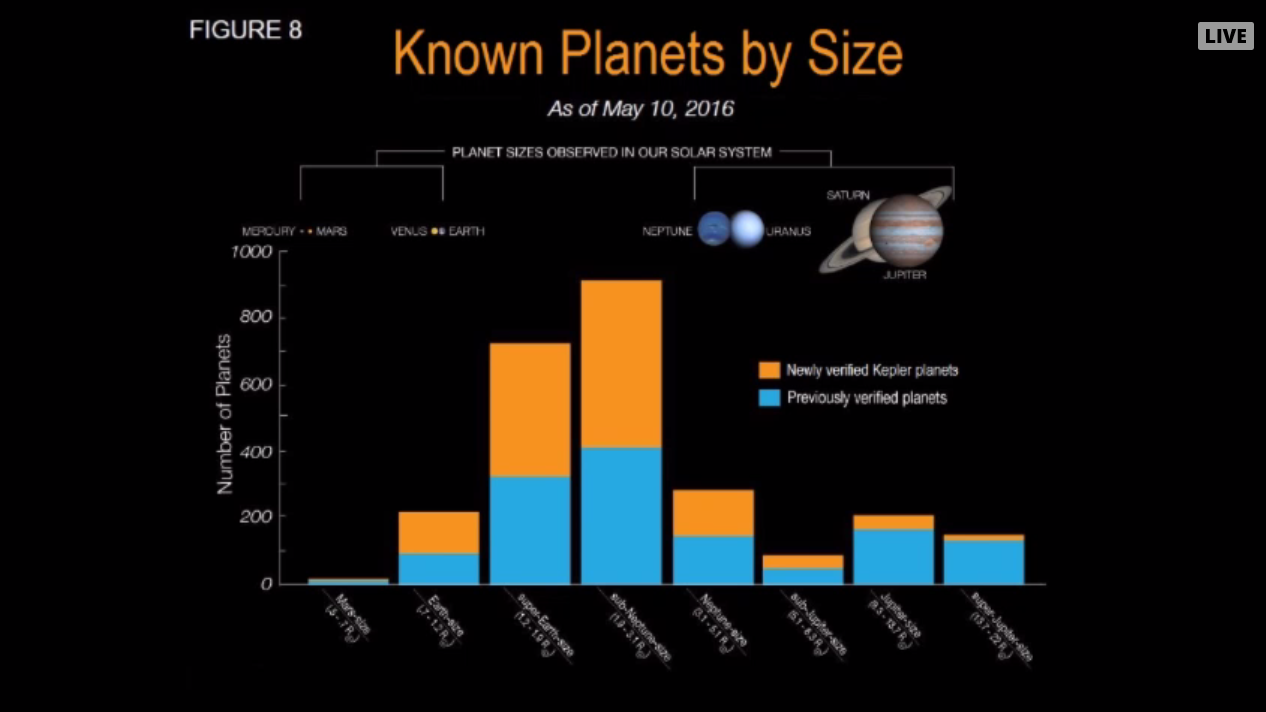

Using this technique, there are now 1,935 confirmed exoplanets in total, with 1,284 of those being new discoveries. Around 100 of the planets are a similar in size to Earth. The research has been published in The Astrophysical Journal.

All of these planets were discovered by the Kepler prime mission, which involved studying around 150,000 stars in a single patch of sky between 2009 and 2013.

Of course, the point of all this planet-spotting is to try to answer the big question "are we alone in the Universe?" To try to figure this out, Kepler scientists can use the transit signal of planets to work out their size and how far away they're situated from their sun, which provides some indication of whether planets could possibly host life.

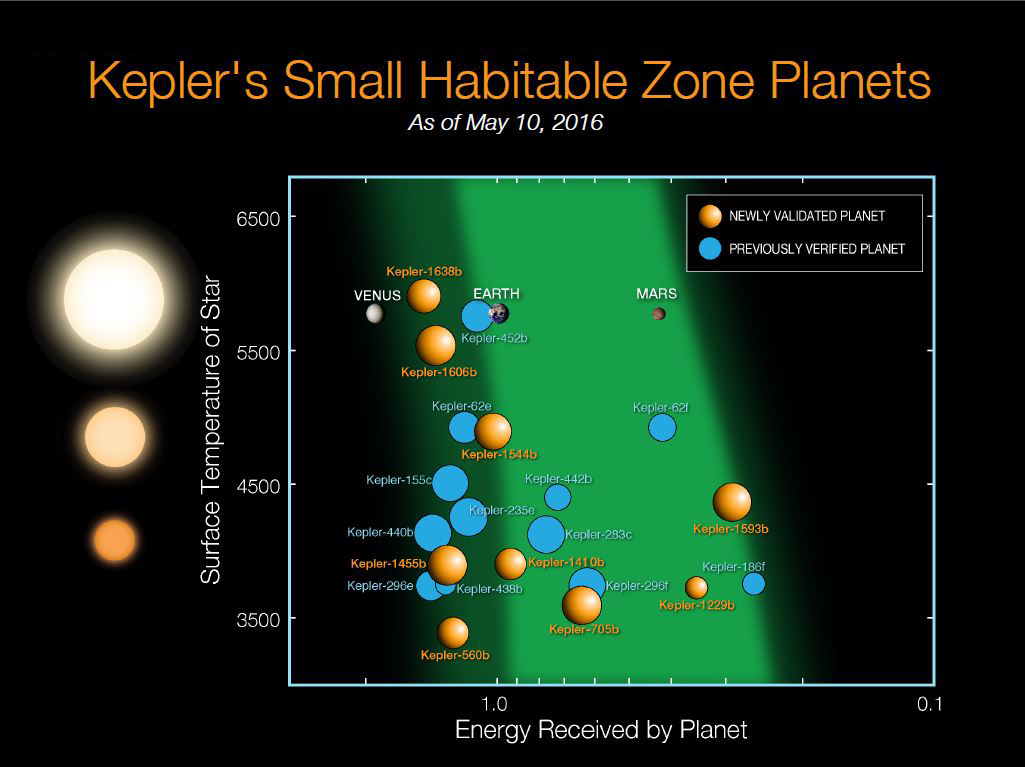

Based on those criteria, the new announcement includes nine planets that are listed as potentially habitable. In this context, that means they're less than twice the size of Earth and are situated in the 'Goldilocks zone' of their star, meaning they're not too close or far away and could potentially contain liquid water.

NASA Ames/N. Batalha and W. Stenzel

NASA Ames/N. Batalha and W. Stenzel

That doesn't mean in any way that these planets do host life, or even that they could. But without being able to study these planets in closer detail, this is the best way we have to assess a planet's suitability for life as we know it.

The ultimate goal is to be able to detect the light coming from one of these potentially habitable exoplanets so that we can analyse the gases in its atmosphere, which will tell us more about whether life ever existed there, or if it could in future.

The sad news in all of this is that Kepler is almost at the end of its planet-hunting mission. It's going to continue to observe strange astronomical phenomena for the foreseeable future, but it's predicted to run out of fuel in around two years, in the Northern Hemisphere summer of 2018.

The baton is being handed to the Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and James Webb Space Telescope, which together will be able to scan even more stars in the night sky, and hopefully tell us more information about the alien worlds orbiting them.

"Before the Kepler space telescope launched, we did not know whether exoplanets were rare or common in the galaxy. Thanks to Kepler and the research community, we now know there could be more planets than stars," said Paul Hertz, director of the Astrophysics Division at NASA Headquarters. "This knowledge informs the future missions that are needed to take us ever-closer to finding out whether we are alone in the universe."

We can't wait.

Live updates from NASA's announcement this afternoon:

12.47pm Patiently waiting for the livestream to start, and this music is pretty terrible.

12.56pm Some wild speculation while we're waiting… a lot of you are excited for this announcement to be about the 'alien megastructure' theoretically orbiting Tabby's star. Based on a study that came out yesterday, that's looking less and less likely. But we could be about to find out that about a potentially habitable star or planet.

OR it could be something else entirely because Kepler also studies phenomena such as black holes and supernovae. So predicting it's a planet-sized announcement might be thinking too small.

So far all we know is… not a whole lot, to be honest. We'll be hearing from:

- Paul Hertz, Astrophysics Division director at NASA Headquarters in Washington

- Timothy Morton, associate research scholar at Princeton University in New Jersey

- Natalie Batalha, Kepler mission scientist at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California

- Charlie Sobeck, Kepler/K2 mission manager at Ames

That combination suggestions that we're in store for a planet-related discovery - maybe the announcement of an exoplanet that might once have been or is now habitable for alien life.

Let's not all get too excited, but come on NASA…

1.01pm Okay here we go, the press conference will be starting "shortly". Stay tuned…

1.03pm Looking at the briefing data over at the Kepler site, seems as though we've just found a whole lot of newly confirmed planets outside our Solar System. Like, 1,284 new exoplanets.

1.04pm "Are we alone in the Universe?" Yes, Paul Hertz, are we?

1.06pm Tim Morton: "Today, we're announcing the discovery of 1,284 new planets in the Kepler mission. This is the most exoplanets that has ever been announced at one time."

1.07pm This more than doubles the amount of known exoplanets, wow.

1.08pm Morton is talking about why the new data dump is such a big deal - there are a lot of objects that can cause "astrophysical false positives", so all new Kepler observations are listed as 'candidate planets'. Traditionally, when Kepler spots what looks to be a planet dimming the light coming from a star, researchers have had to follow up each one individually with ground-based telescopes, which takes a lot of time and money.

1.10pm "Imagine planet candidates as bread crumbs. If we drop a few on the ground we can pick them up one by one. But if you spill a whole bucket full of small crumbs, you're going to need a broom to clean them up." What they've come up with is a scientific broom - a new technique that identifies planets en masse.

1.11pm This new technique works by looking at whether the signal looks like a planet, and then rates how likely imposter planets are in the Universe. This gives them a reliability score between 0 and 1, and if something comes up over 99 percent likelihood they call them validated planets.

1.12pm What are these new planets like? This is their size… that's quite a few Earth-like ones!

1.14pm And this is how the new planets fit in compared to all the Kepler candidates so far:

1.15pm These new planets were all found in the area of sky that Kepler trained on between 2009 and 2013.

1.15pm The new technique is going to be very valuable in the future to help us really understand how many planets - habitable and not - are out there in the Universe.

1.17pm Here's what we all want to know - nine of the planets announced today are potentially habitable. That means they're similar in size to Earth and they're in the 'Goldilocks Zone' of their planet, so liquid water could be present.

1.19pm Of particular interest is Kepler-1229b (the Earth-sized orange planet down in the bottom right corner of the image above), says Natalie Batalha. That's because it's similar in size to Earth but close to the middle of the habitable zone. Kepler-1638b looks good, too.

1.20pm Wow, this is one of the last planet data dumps for Kepler, as NASA moves towards using the new Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) and James Webb.

1.23pm Back to Paul. The ultimate goal now is to detect the light from a potentially habitable exoplanet and be able to analyse the gases in the atmosphere of the planet, which could tell us if life exists there and answer the question 'are we alone in the Universe?'

1.25pm We're sad that Kepler will no longer be hunting down planets for us, but it's still going to be observing other phenomena in the Universe. "It's been a privilege working on Kepler," says Charlie Sobeck.

1.25pm Here's NASA's planet-hunting plan going forward:

1.26pm Question time! Use the hashtag #AskNASA to ask your own!

1.30pm Unrelated thought: imagine if we actually had the technology to perform flybys of these planets. Maybe like this system proposed by Stephen Hawking.

1.32pm How many of these planets are habitable? It's hard to know, but this new data dump adds nine planets that are not only in the Goldilocks Zone but also are the right kind of size to be potentially rocky.

1.33pm How do we plan on studying these planets in more depth after this announcement? TESS + James Webb is the dyanmic duo that will give us more detail on these new exoplanets, as well as Earth-based telescopes.

1.40pm A whole lot of questions about potentially habitable planets and the overall answer is: we still don't really know much.

1.48pm What's the difference between TESS and Kepler? While Kepler looked at one patch of sky in detail for four years, TESS will look at closer stars across the whole star for 30 days each. "TESS is looking at closer stars but for shorter periods of times."

1.57pm Aw, Kepler only has an estimated two years left of fuel.

2.15pm Great question: why should kids care about this? What does this mean for the future of science? Natalie's giving us some philosophical answers: "We're going to change the way you see the Univese. When you look up in the sky, you're not just going to see pinpoints of light and see them as stars, you're going to see pinpoints of light and see them as planetary systems." It also tells us more about who we are and how we got here. Hell yes.

2.16pm Okay, it's all wrapped up. Thanks so much for watching with us, guys!